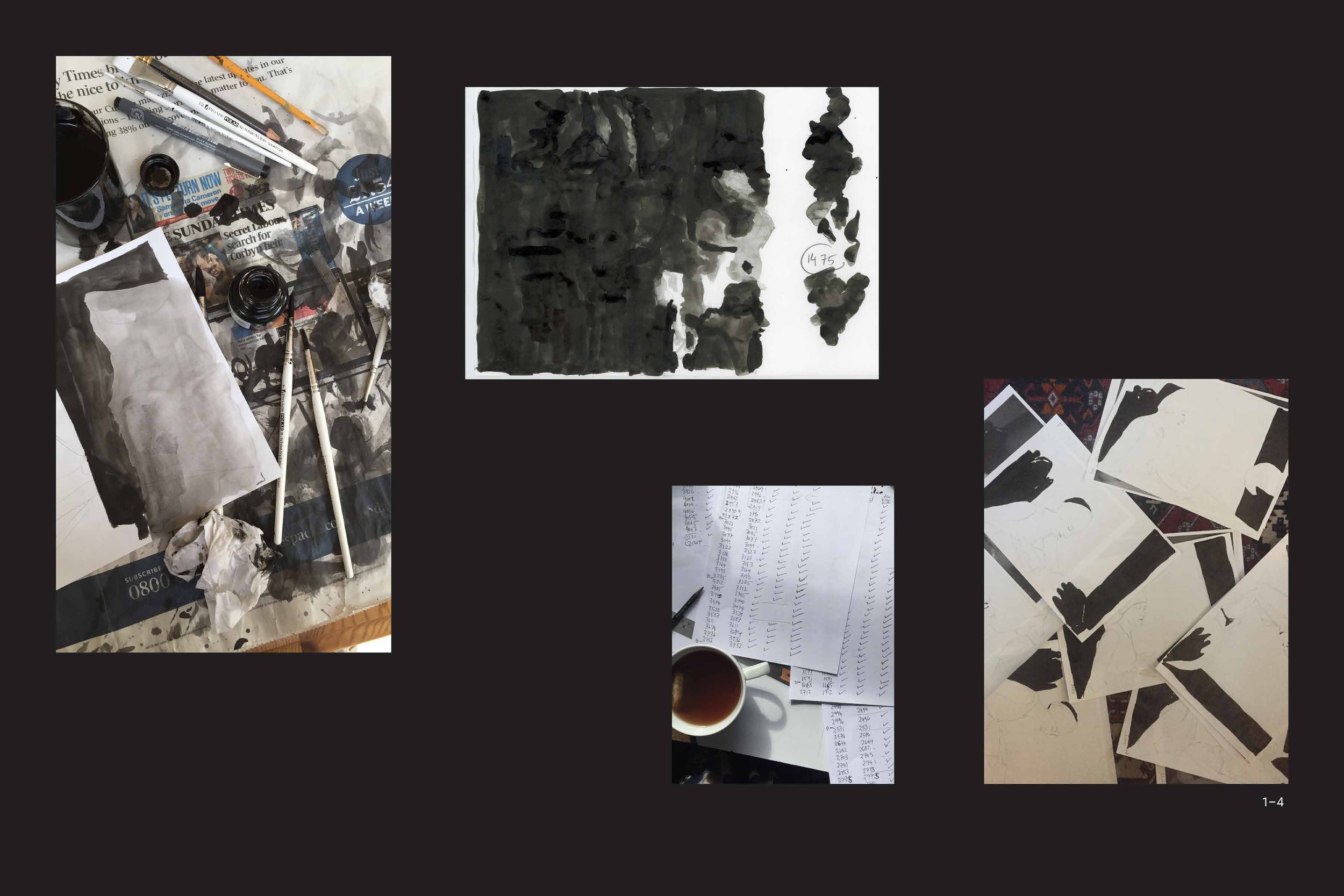

Fall of the House of Usher II is a handmade dataset of over two hundred individual ink drawings of Watson and Webber’s 1929 silent film, Fall of the House of Usher that formed part of my process of creating the film of the same name. The creation of these drawings required an immense amount of labour. Unlike pressing a button, making a drawing is a commitment to spending a certain amount of time with a particular image on a sheet of paper. I deliberately chose to work with ink - early GAN produced imagery has a slightly painterly quality that is reminiscent of it and as a material has randomness already inherent in the medium. It is very difficult to control and the differences between pictures of the same scene are amplified. It is also unforgiving, goes everywhere and escapes. Traces of humanness - fingerprints appear in the dataset, somehow out of place in a digital work, but there.

Drawing is interesting in the context of machine learning - and there was at the time of production debate about whether GANs would be able to produce art. Drawing is both a noun and verb - for me the act of drawing does multiple things, including a very human process of trying to collapse time, memory and even space - so that while a machine might be able to produce drawing as a noun, it is not ever able to produce drawing as a verb. William Kentridge, a South African visual artist, has written how “you can’t instantly create 400 drawings” but that is just not true anymore. Machine learning now allows us to do things that fifteen, twenty years ago would have been in the realm of fiction. Chess used to be seen as essentially human, but now machines can do it this view has changed. Will the same thing happen to drawing? Already what drawing means is changing.

Drawing after the GAN generated images was incredibly difficult - the logic of the world is there but not quite there (shadows are not quite right, twists in fabric do not hang as expected). Style in drawing always evolves but because I drew in this style for so long, it has changed how I now draw and paint a picture. I now start to add in artefacts and my line has changed. It is odd to have two different GANs that now have my style at two separate moments in my life frozen into them.

The construction of the datasets to make Fall of the Usher I lead to a loop between copying and repetition, both manually and by the machine, between the labour intensive nature of creating the drawings for the training set and the speed of the algorithm producing the stills. Allowing the dataset to be displayed as an artwork gestures at this. The project is no single one piece - it becomes harder and harder to get back to the point of origin. The dataset shown is loser and wilder than I ever would have been able to make myself. Entropy and decay are incredibly beautiful. Making it reminded me of a short story by Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius, a short story by Borges, is an account in part of a fictional country of Uqbar where “the duplication of lost objects is not infrequent” but these duplications - hronir - “were the accidental products of distraction and forgetfulness” (my missing chair, lazy way of drawing eyes) “no no less real, but closer to expectations” but which over times and cycles become comes “a purity of line not found in the original”. It is my work but also not my work - recognisably me but nothing I would have been able to do by myself.