The Breathings of the Moon

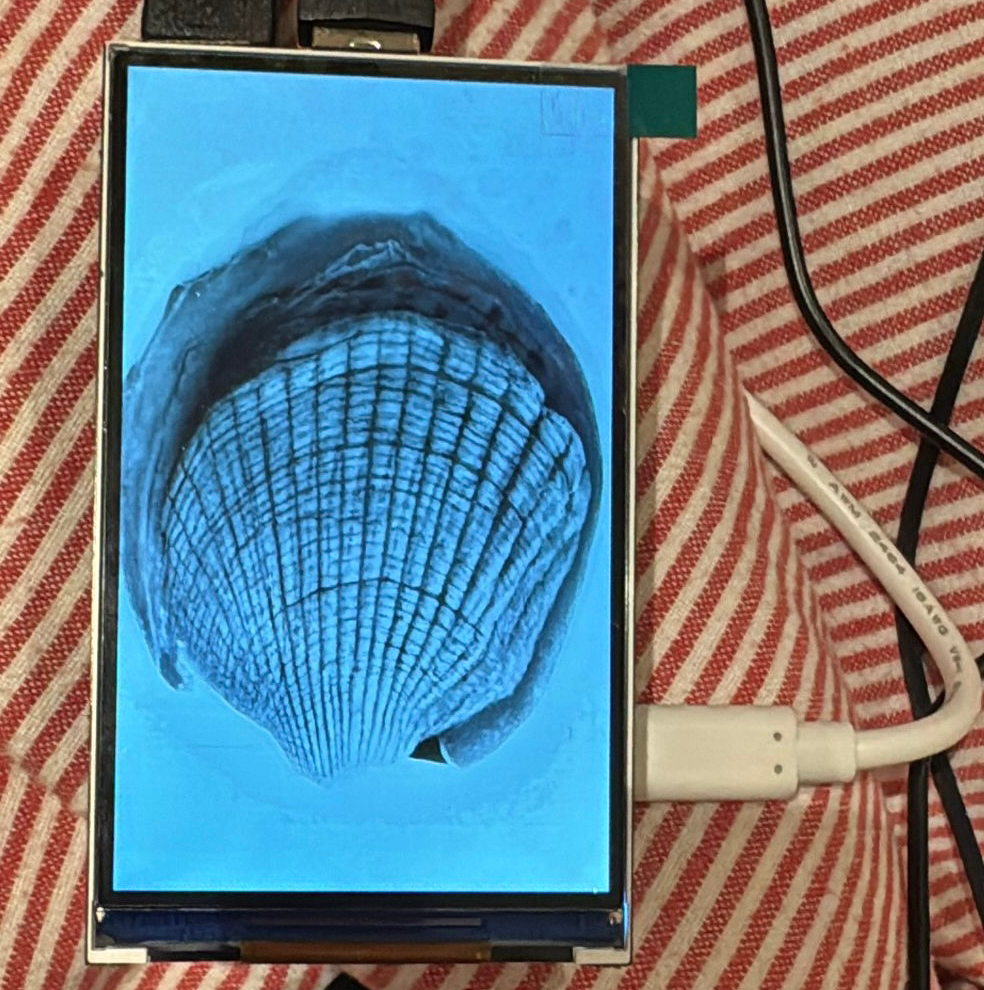

This collection is made up of AI generated shells, trained on a dataset of photographs I have taken over many years. The images are created using a combination of different neural networks, the fidelity and detail sharper than I was able to achieve four years ago) but still retaining on close inspection some of the weirdness and uncanniness that draws me to working with machine learning. The Thames is a tidal river with two tides a day. The protocol inside of the smart contract dictates that the image of the shell will only be visible at low tide; at high tide the image will be entirely covered in black. Each different token is assigned a different location along the Thames, from the head of the tidal river to the mouth, so that each one reveals itself fully at slightly different times. Only when the shell is fully visible (around an hour) will the owner be able to sell the work. This locking and unlocking of the work and ebbing and flowing of the image will happen twice a day, every day for twelve years when the project will conclude. I have always been interested in introducing friction into marketplaces, particularly when it asks a buyer or seller to slow down and step out of traditional exchange dynamics. Rather than being an asset kept in a wallet to accumulate value and traded, the work asks for attention if it needs to be sold. Only by looking, and waiting, can someone determine if it can be. In a world where technology increasingly brings instant satisfaction, I want to work against this and to encourage the act of observation and seeing.

Process and Research

But the most admirable thing of all is the union of the ocean with the orbit of the moon. At every rising and every setting of the moon the sea violently covers the coast far and wide, sending forth its surge, which the Greeks call reuma; and once this same surge has been drawn back it lays the beaches bare, and simultaneously mixes the pure outpourings of the rivers with and abundance of brine, and swells them with its waves. As the moon passes by without delay, the sea recedes and leaves the outpourings in their original state of purity and their original quantity. It is as though it is unwittingly drawn up by some breathings of the moon, and then returns to its normal level when this same influence ceases. Opera de Temporibus, Section XXIX, the Venerable Bede, 703 AD. It is part of my ongoing interest in linking history and technology, objects and speculation and the nature found on the river Thames. I have been collecting shells from the foreshore of the Thames, one of the largest open archaeological sites in the world, right in the shadow of one of the centres of global financial capitalism for many years now. The act of collecting, cataloguing, training, generating, and tokenizing these shells creates a new form of value in the shadow of the old. But these shells have a history of their own, far beyond their use as mere items of exchange. Shells have been used as stores of value and tokens of ritual significance for thousands of years. Before the rise of modern financial systems, shells were used as money on nearly every continent on earth. After the rise, shells were even the subject of a speculative mania (much like tulips) where European collectors spent enormous sums of money on rare shells in the 18th and 19th centuries. The title of the series references Bede, an English monk, who amongst other things was deeply interested in and influential in creating an ecclesiastical calendar system for the country. Part of the way that he did this was through observation of the world as he saw it - solstices, equinoxes, moons. Much of my work is also to do with cycles and knowing through things unfolding over time. It feels fitting for me to use his quotation in this work that questions what happens when natural cycles collide with manmade systems.

Exhibition Venues

Dissemination

The fifteen editions also come with an almanac. MORE