Bloemenveiling, 2019

website, smart contracts, NFTs, GAN generated video and bots. In collaboration with David Pfau,

Website: http://bloemenveiling.bid

“[Tulip Mania meant that] the order of the stock market was introduced into the order of nature. The tulip began to lose the properties and charms of a flower: it grew pale, lost its colours and shapes, became an abstraction, a name, a symbol interchangeable with a certain amount of money.”

- Zbigniew Herbert

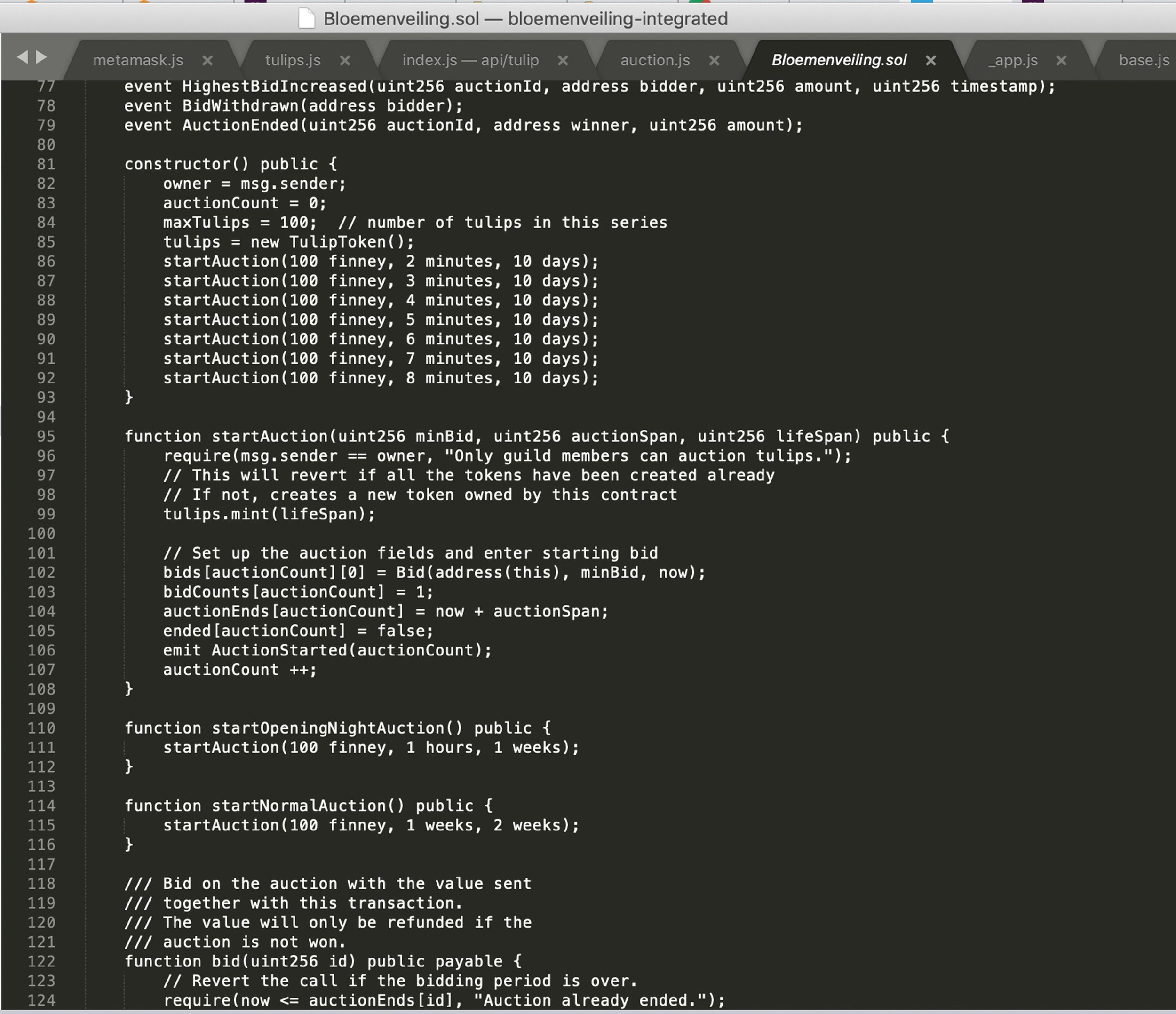

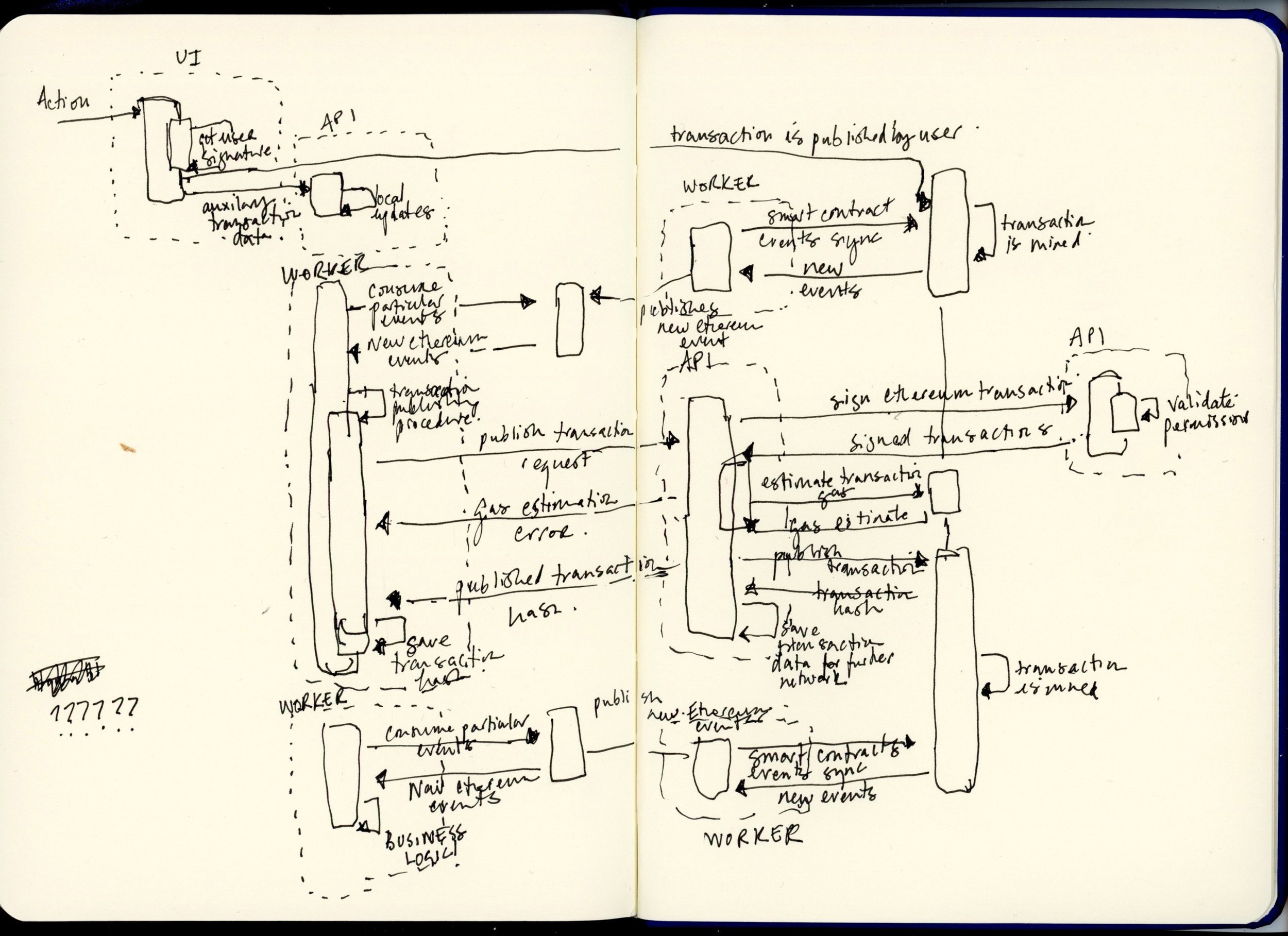

An early piece of NFT art, Bloemenveiling was an online auction of short GAN generated videos of tulips; it used smart contracts on the Ethereum network to sell the work and bots to help drive speculative prices. The piece was made in collaboration with David Pfau, an artificial intelligence researcher, and is the third in a series of work that looks at the relationship of the tulip to speculation, hype and value. Through the use of these types of technologies, which are increasingly embedded across different types of markets, it interrogates the way technology drives human desire and economic dynamics through artificial scarcity. It was created as an artwork, for a gallery show, but was a fully functioning distributed app (dApp), existing as a working example of what it also critiques.

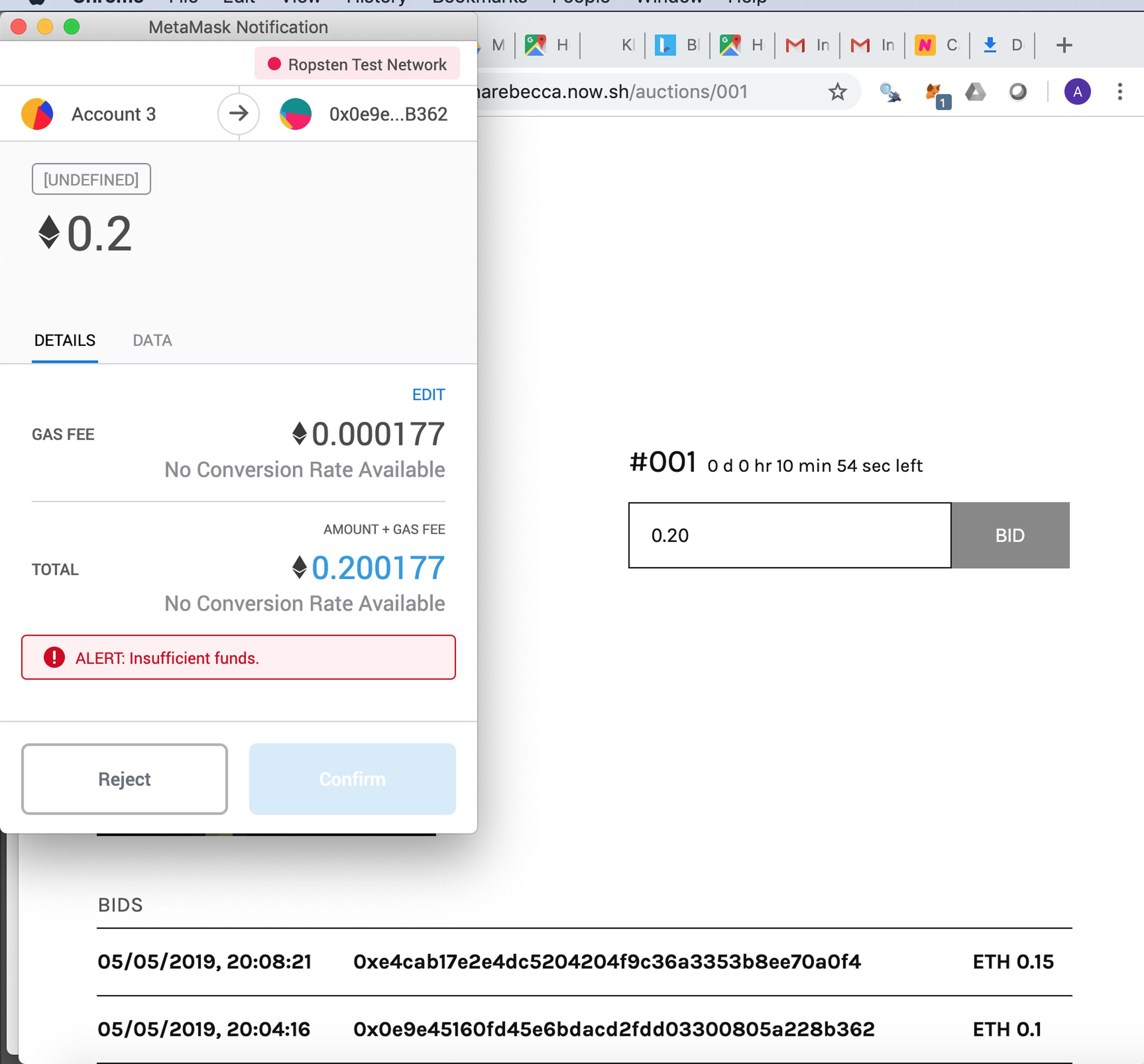

The blockchain is an abstract concept and does not lend itself immediately to visual or experiential expression. It is a series of complex, interconnected systems that are usually hidden from the end user. The process of creating our own Ethereum smart contracts and web front-end for auctions uncovered the massive inefficiencies and complexities inherent in creating a distributed app that are obscured if using a third-party platform. While a dApp looks and feels much like a normal web app – but much slower – the backend is often a tangled nest of components necessitated by the convoluted process of interacting with a blockchain. An inefficiency that was highlighted by working in this way was the enormous amount of energy needed to run the Ethereum network - minting a single NFT with Ethereum is estimated to require as much energy as a typical European household uses in a month. The extraordinary amount of duplicate effort required to validate work in a trustless system means that several supercomputers’ worth of computational power is used to build something that is about as fast as a 1990s mobile phone. The commodification of a replica of the natural world ends up consuming far more power than the cultivation of an actual natural flower.

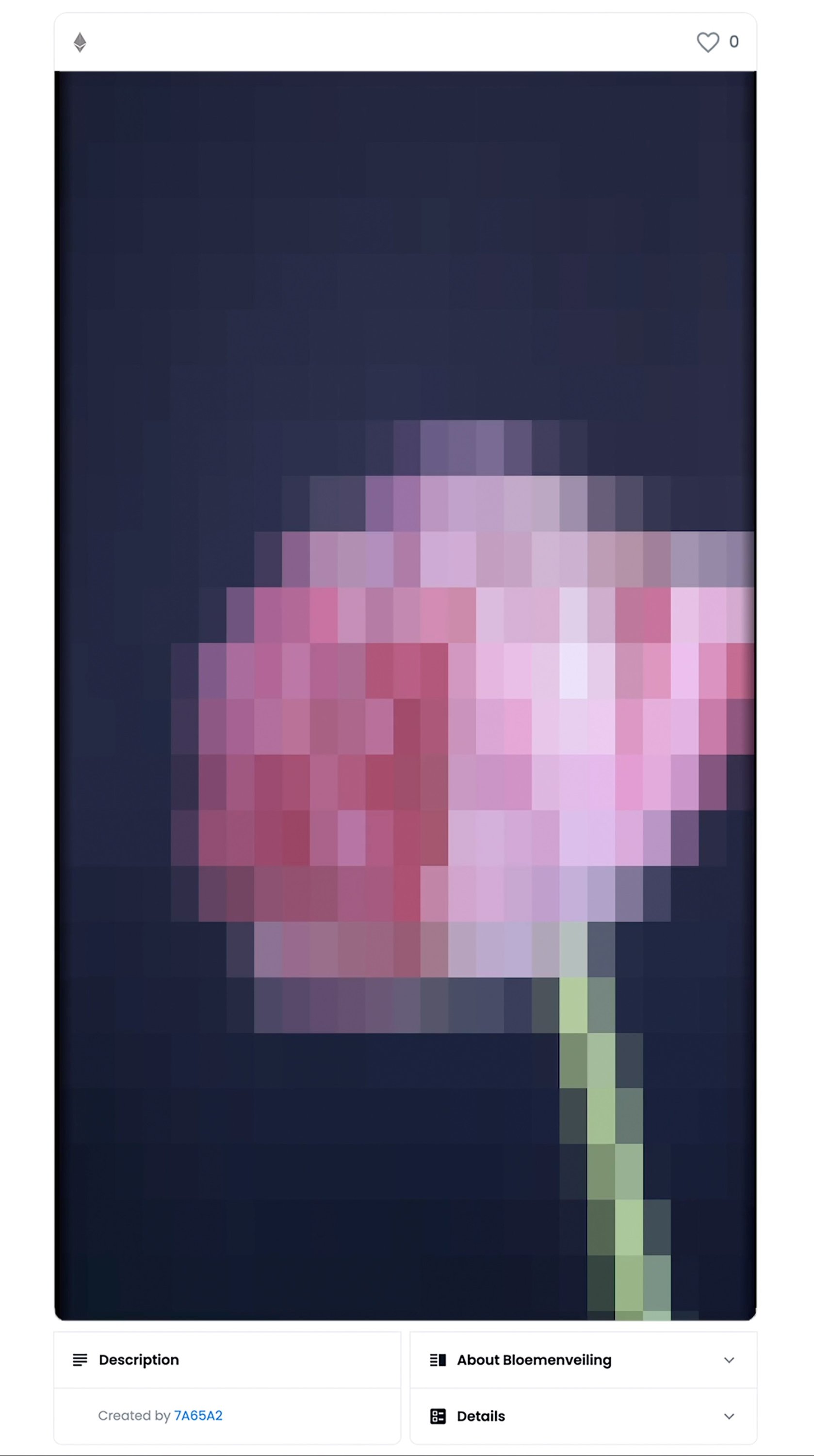

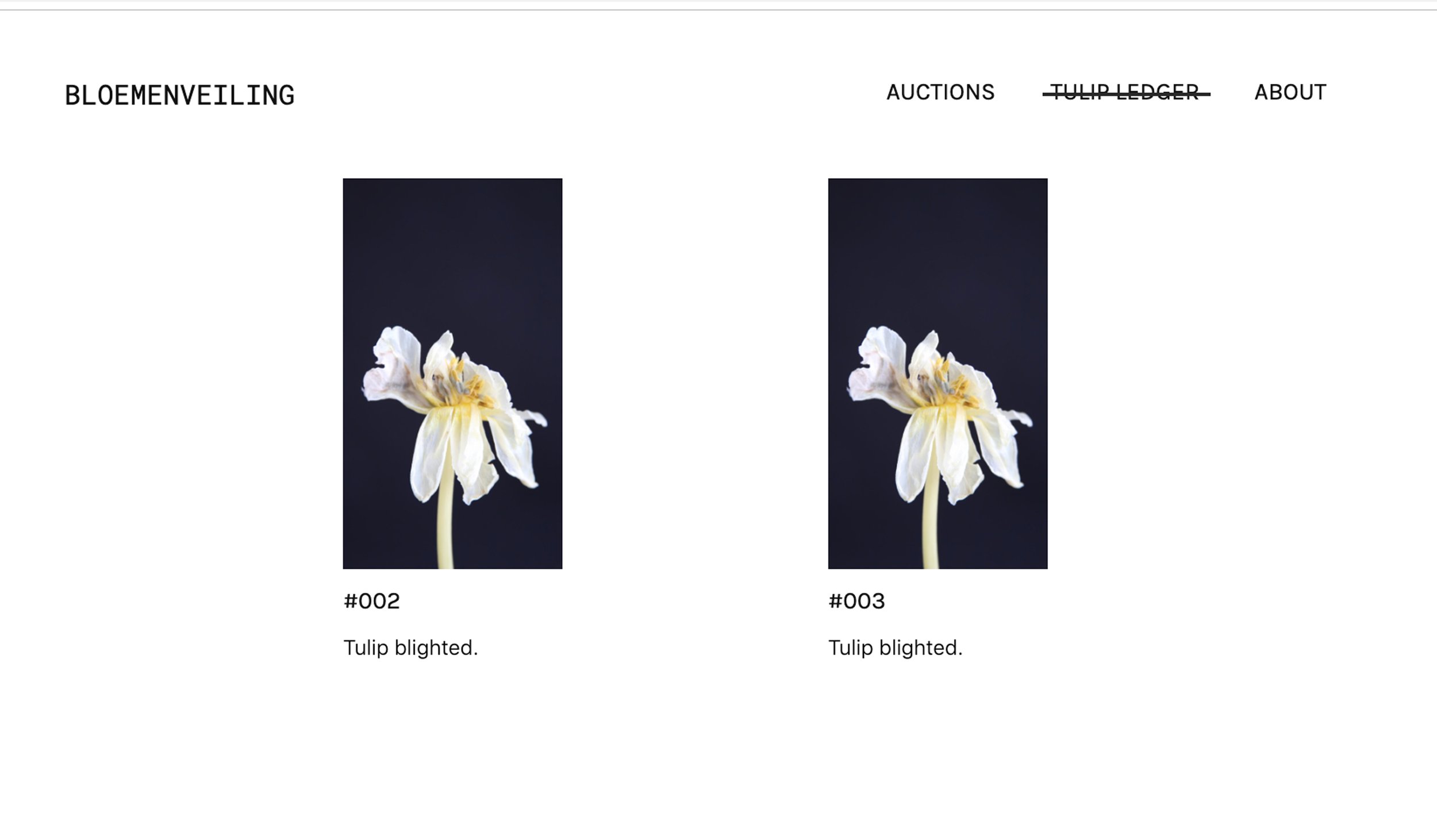

A major use of blockchain in the art world is to introduce scarcity to digital works. This is in inherent tension with how these types of works should naturally behave: infinite tulips could be produced by the GAN, but the ones that are valuable are only the ones that are associated with the finite supply of tokens. We wanted to exaggerate this artificial scarcity that is a critical part of the blockchain process by making the tokens self-destroying after a fixed amount of time. The smart contracts which enabled the sale and defined the work in the technical process were used to mirror how real tulips behave so that the decay and impermanence of the natural world was reintroduced into the digital world. The contracts were programmed to show the video, or bloom, for a week - approximately the same amount of time a cut tulip lasts - before the tulip became “blighted” and disappeared from the owner’s view. This allowed the viewer to appreciate it as a work of art as opposed to a commodity, by making it temporary and therefore difficult to trade, activating an unintended possibility that is built into the protocol and negating the original intent of NFTs as speculative assets. There was only one way around this blight. After the end of the week, if the owner were never to attempt to view the video work again, then the token would never be burned, preserving its speculative value but existing only as a signifier of the original work.

When we made this piece, it seemed obvious to us that NFTs would be used as a way to securely grant the owner of a token the right to view a given artwork. After all, the token itself was little more than a digital certificate that had no inherent relation to the artwork it was meant to represent. Never did we imagine that there might be a market for NFTs even if the artworks which they represented could be freely viewed and shared by anyone. The logic of commodification proved more adept and malleable than we could have foreseen even a few years ago. It seems certain to mutate into yet stranger forms.

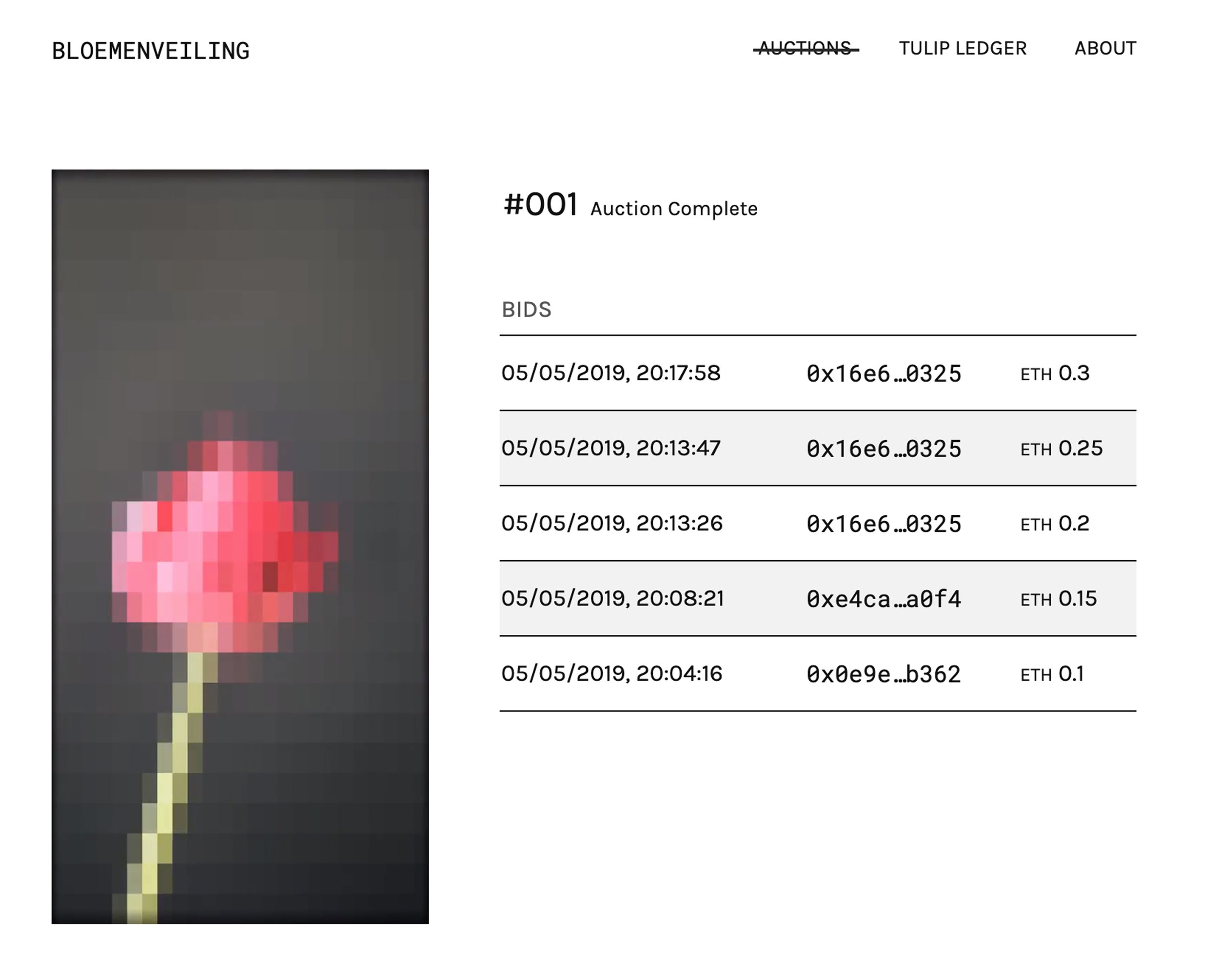

We wanted there to be a strong element of chance in the marketplace we were creating. At the height of tulipmania bulbs were not bought or sold as physical objects but rather as paper contracts – purchasers would have no real knowledge of what would eventually bloom. On our website the videoworks, of varying quality and interest, were only displayed pixelated until the contract was unlocked by the highest bidder. This created an element of chance in the auction, which was then further heightened by the introduction of non-human agents: bots who also bought and bid on pieces driving demand in much the same way that automated trading algorithms drive modern financial markets. The flower markets for which the piece is named have now evolved from their roots in the Dutch taverns of the 1630s, into something much like modern stock markets, complete with technologically sophisticated platforms and proprietary data. It felt appropriate therefore to bring the auction from being governed by the rules of the seventeenth century to that of the twenty-first, where prices are now increasingly manipulated by machine learning. So much of our consensus reality today is being created by software we hardly understand – financial markets, algorithms – and it becomes harder and harder to sort out where the human influence is.

Bloemenveiling is a functioning decentralized application part of a wider project connected to Mosaic (Virus), 2019 and Myriad (Tulips), 2018, which explore different aspects of the same idea. Exhibited at HeK (2019), Eden Project (2019) and Mexican City Art Week (2019).

Research and Process (2018-2019)

….It became customary to indicate the weight of each bulb when it had been returned to the ground. Weights were given in azen (“aces”), an extremely tiny unit of measurement customary with goldsmiths. From this it was only a short step to selling tulips not by the bulb, but by the ace. The new system also meant that prices increased much more rapidly than before. Since most tulips grew substantially in size once planted in the ground, it was almost certain that the value of the bulb would increase significantly from the time it was planted until it was lifted months later.

Records from the tulip trade reveal how just dramatically the money invested in a single bulb could multiply. For example, a Viceroy tulip, grown in the garden of an Alkmaar wine merchant named Gerrit Bosch just outside the city walls, weighed 81 aces when it was planted in the autumn of 1636; two years later it had grown to 416 aces, marking a fivefold increase. In effect, the azens became like futures…..

Short moving image digital fragments of tulips created by generative adversarial networks are sold at auction using smart contracts on the Ethereum network. Each time a tulip is sold, thousands of computers around the world all work to verify the transaction, checking each other's work against each other. Even if the website for the auction shuts down, a permanent record of tulip ownership will always exist.

Still life with flowers (1639), Hans Bollongier. | Painted shortly after the stock market crash in 1637 when many went bankrupt due to the speculation in tulip bulbs.