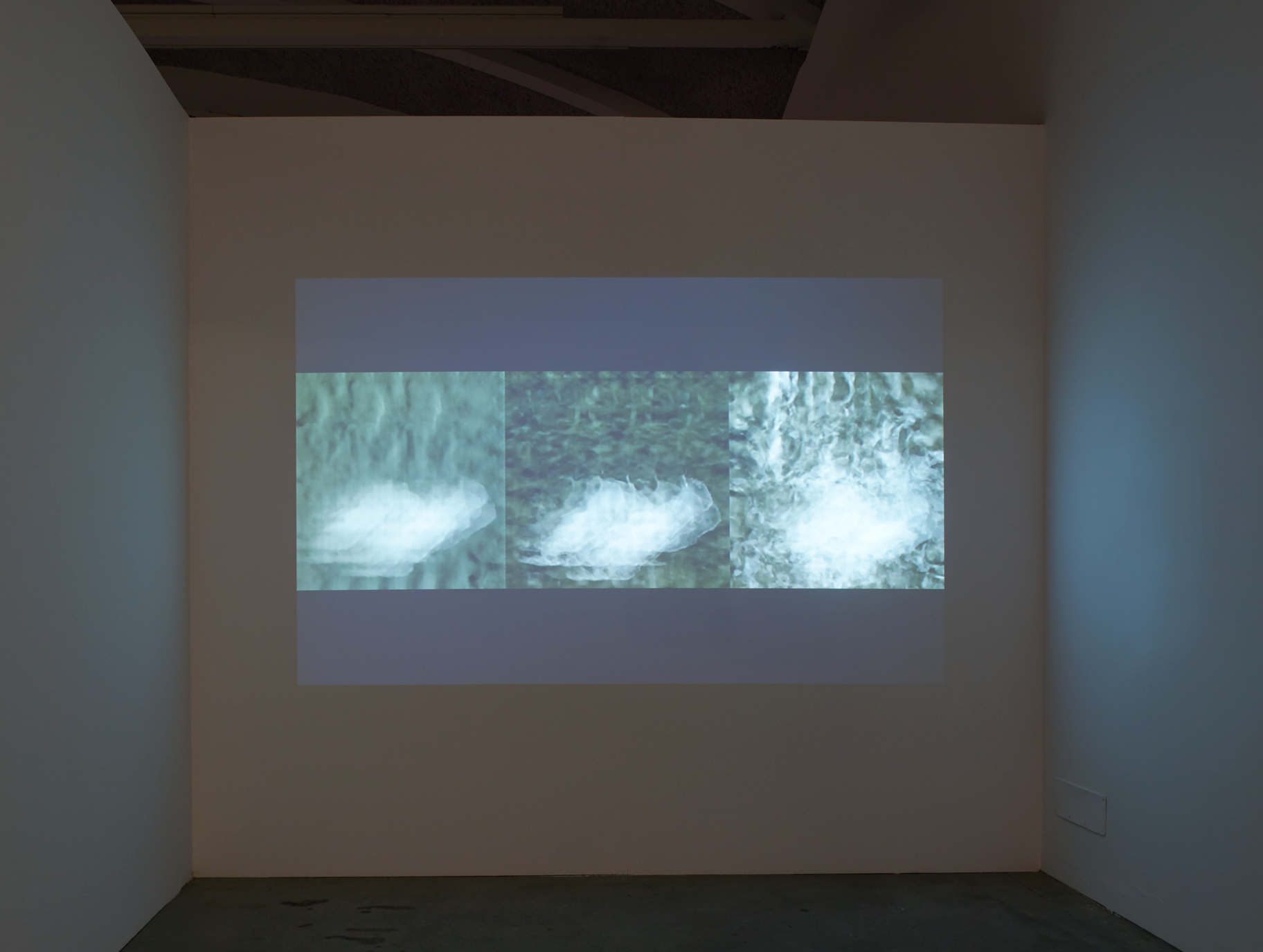

Fall of the House of Usher I, 2017

Single channel video installation (made with a series of interconnecting GANs)

Duration: 12:00

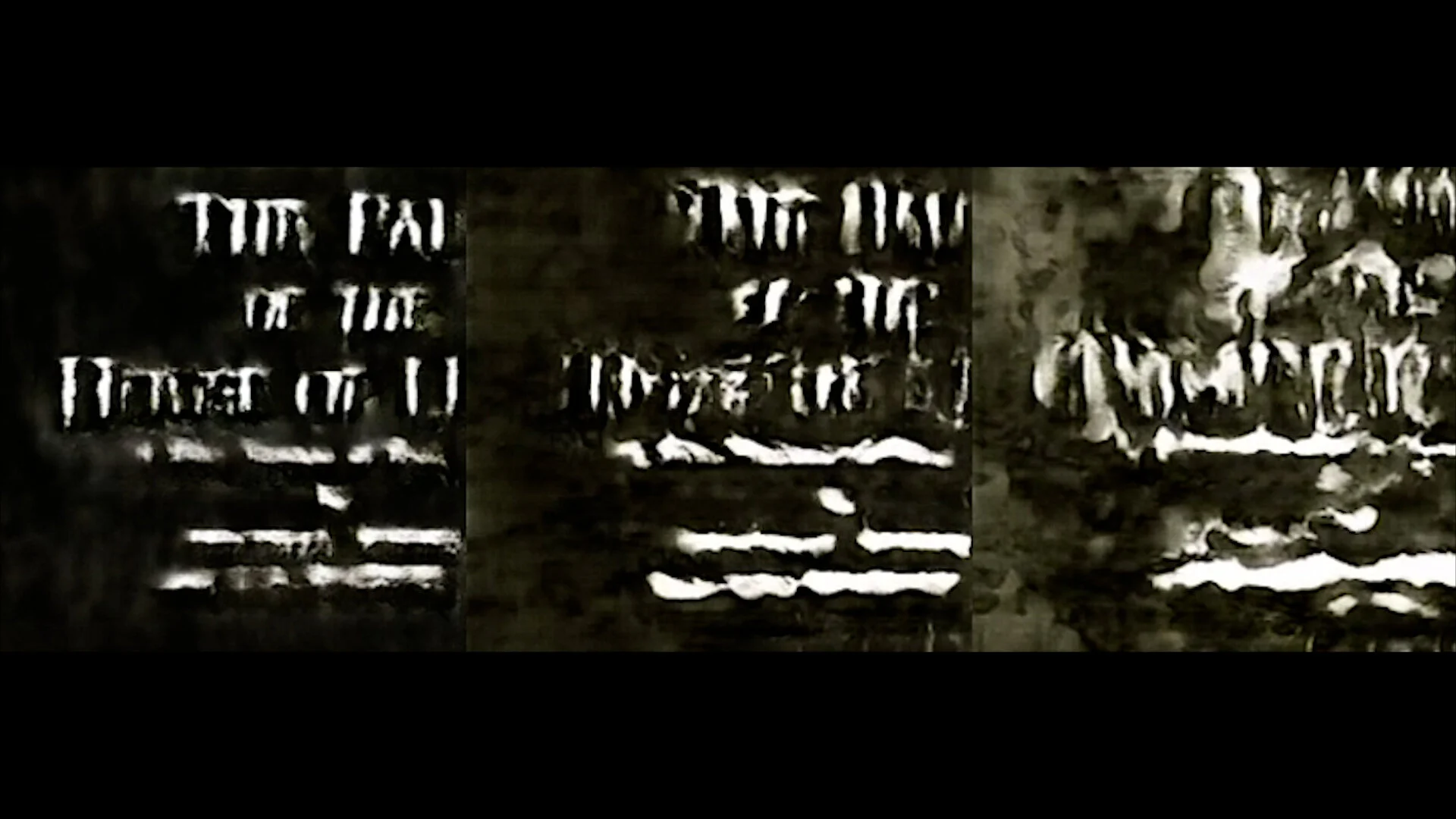

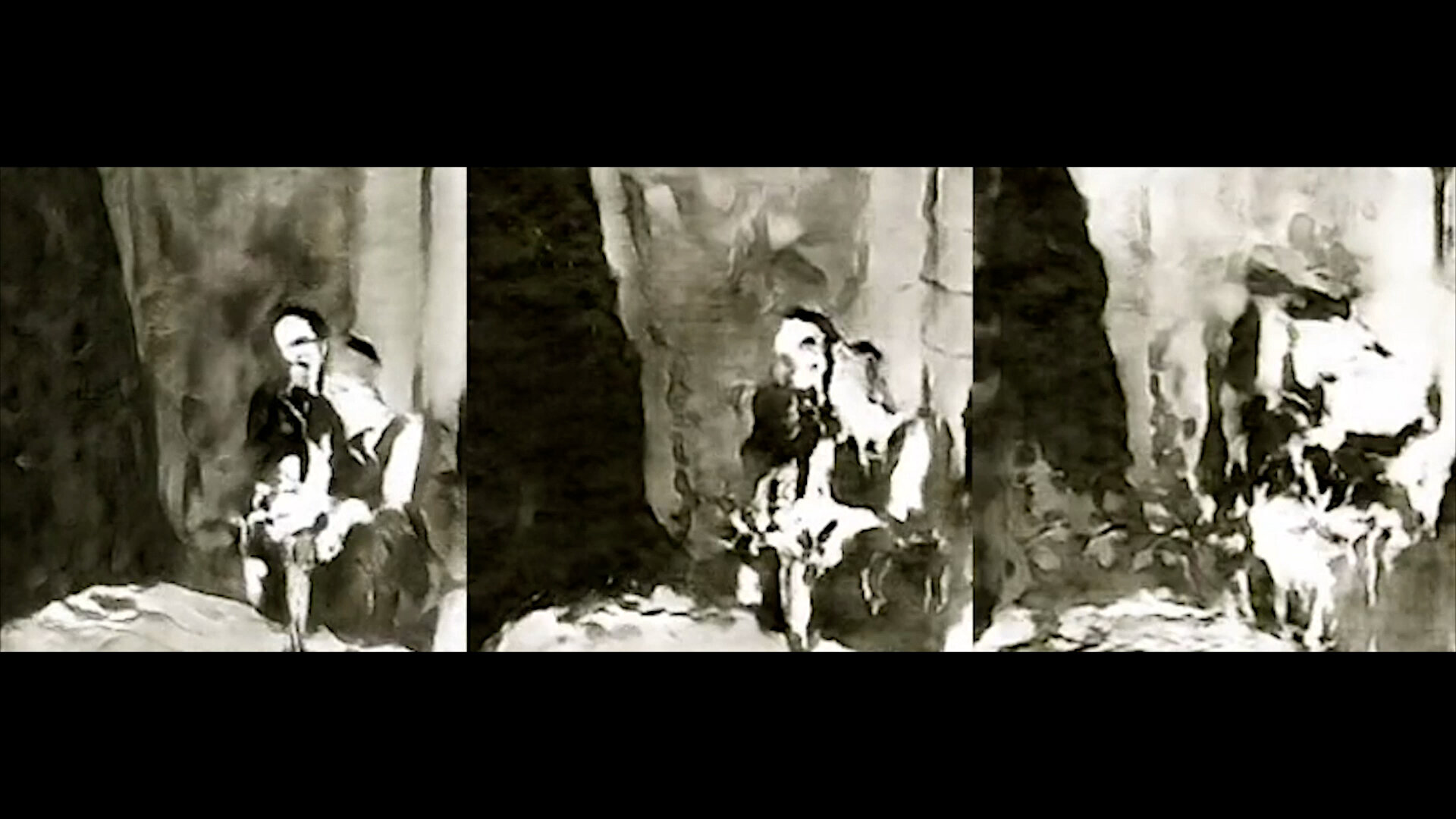

Fall of the House of Usher I (2017) is a 12 minute animation, exploring Watson and Webber’s 1929 silent film adaption of the Edgar Allan Poe short story from 1839; a tale about decay and destruction. The work fuses two hundred ink drawings made with the technical process of machine learning to accentuate the horror story in the original film and notions of fear around artificial intelligence itself. Each still has been generated by a general adversarial network trained on original ink drawings.

A hand made training set of two hundred ink drawings inspired by the 1929 silent film version of The Fall of the House of Usher, was processed using a series of interconnected general adversarial networks. The end result was an animation created from a series of machine made stills. By manipulating the reciprocity and feedback between the original film, drawing and this form of technology, the film’s original motifs are Ridler heightened and intensified by liberating fugitive aspects of memory to create a sense of the uncanny that is partly machine-made.

This work is the predecessor to Fall of the House of Usher II (2017), a display of the artist’s ink drawings which serve as the dataset for the animation. Exhibited at Ars Electronica (2017), the V&A Museum (2018), Nature Morte (2018) and the Centraal Museum (2018).

Please email for a link to the film.

Research & Process