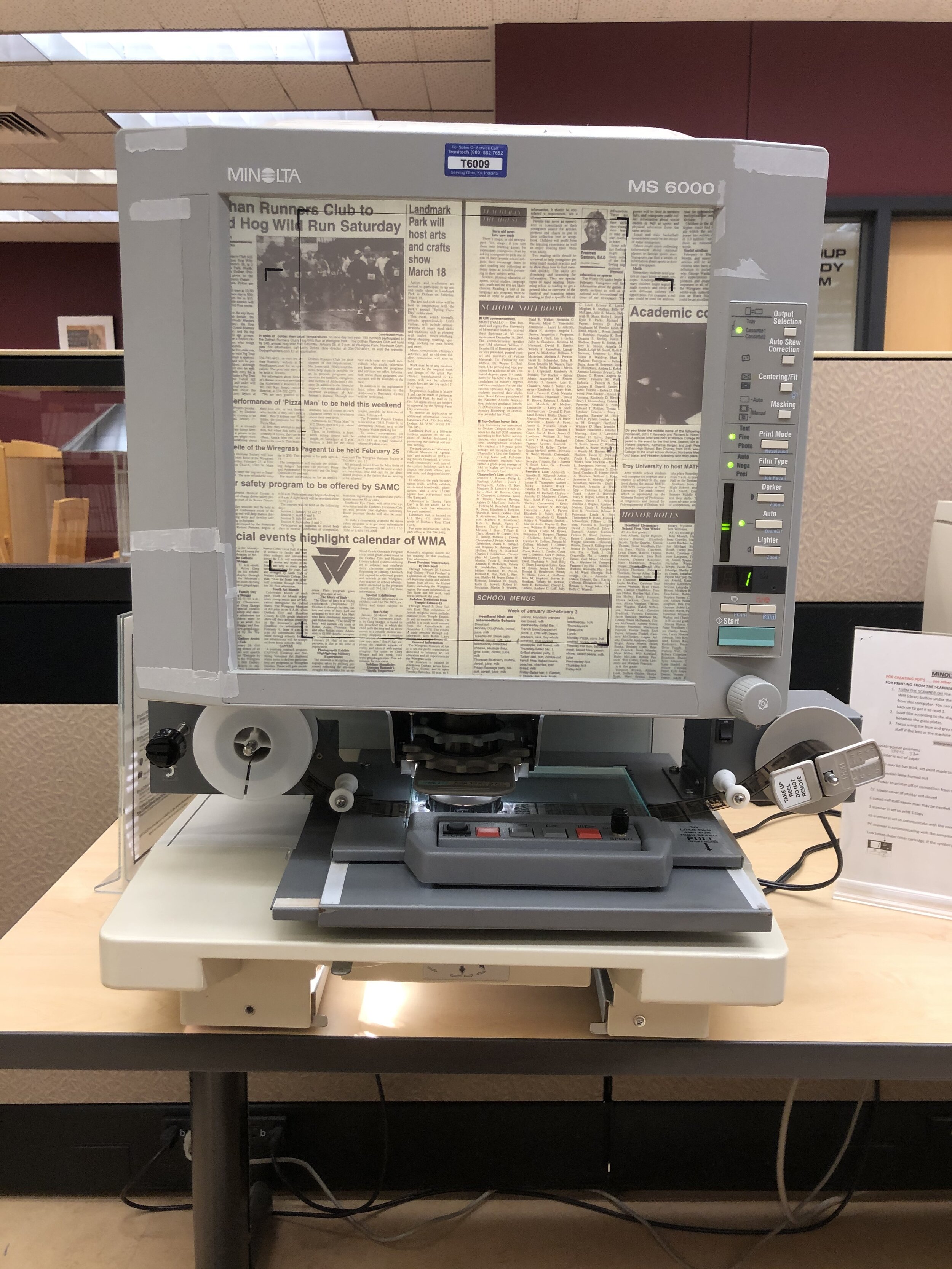

‘Missing datasets’, a term coined by Mimi Onuoha to describe “blank spots that exist in spaces that are otherwise data-saturated”, is a good phrase to use for the lack of these papers. Given how pervasive news is in everyday life, it feels axiomatic that the final editions should be kept somewhere in some form - and indeed there are traces. Occasionally it will be possible to find them on local library networks (Colorado), and there are a handful of websites that have been left up, frozen in time, and facebook pages that stopped posting updates many years ago, and now have been overtaken by far-right commentators posting their own links. Some only now exist on microfilm, which is impossible to access without time, money, and the ability to travel to a location which has the appropriate equipment. This absence has an impact: without a record of a local paper institutional memory of place is lost, as well as access to information. Research has shown that people without access to local news are less likely to be engaged with their communities and places to feel the impact of local government not being scrutinised and, as a result, be more susceptible to fake news.Professor Ron Heifetz describes a newspaper as “an anchor” because it “reminds a community every day of its collective identity, the stake we have in one another and the lessons of our history”. Without an accessible archive, all of this collective identity is lost.

Economics is the shadow story in this piece. Newspapers close because of lack of revenue; those that survive are purchased by private equity firms (the largest 25 newspaper chains own a third of all newspapers, including two-thirds of the country’s 1,200 dailies) who load them with debt and slash the workforce until they also have to close. This indifference has another impact: these smaller papers stop archiving themselves, either digitally or physically. It costs money to create an archive - one librarian estimated that it was $1 per page per newspaper - that is just not being provided. The latest estimate suggests that around 90% of newspapers remained unscanned but the cost and effort of keeping the original physical version means that they are often thrown away.

This project was meant to be an antidote to this - conceptualised to draw together for the first time these editions, to see how the data combined, in a set, shows much more than the individual newspapers do: the breadth and scope of America from news and the repetition of small scale stories. But now Final Edition, through a lack and an ought, brings out the scale of what has been lost. Making this piece has been a difficult analogue and physical process, requiring visits to libraries in state, and searching through microfilms which may or may not be labelled correctly. But it has also been a surprisingly social one - rather than merely scraping a website and downloading the results, it has been the calls and emails and connections with people who either built the newspapers or who have been trying to archive them since, who understand what has been lost and want to try to correct it. It has been both incredibly bureaucratic - endless filling out request forms and waiting to hear back - but also full of so many points of human connection. Data is often thought of as being cold and sterile and algorithmic, but really, a lot of the time it is the traces of someone’s life but just made tractable. Final Edition works with this and emphasises it: rather than becoming a dataset that has been constructed by scraping other websites, formatted and ready to be used as a training set, it is the opposite. A small series of images that have been brought together not because they are neatly categorised and findable but because of the knowledge and relationships that sit outside of these systems, and becomes an acknowledgement of the difficulty of creating datasets when they sit outside what is easily saved and the work that needs to go into finding something that is not easily found.